Fifty years after the fall of Phnom Penh to the rebel army of Khmer Rouge, the events of April 17, 1975 continuous to broadcast a long shadow on Cambodia and its political system.

Leaving the spill of blood and the chaos of the propagation war in neighbor Vietnam, the radical peasant movement of Pol Pot rose and defeated the regime backed by the United States of General Lon Nol.

The war culminated five decades ago on Thursday, with the forces of Pol Pot sweeping the capital of Cambodia and ordering the more than two million people from the city to the countryside with little more than the belongings they could carry.

With the abandoned Cambodian urban centers, the Khmer Rouge embarked on the reconstruction of the “zero year” country, transforming it into an agrarian and classes society.

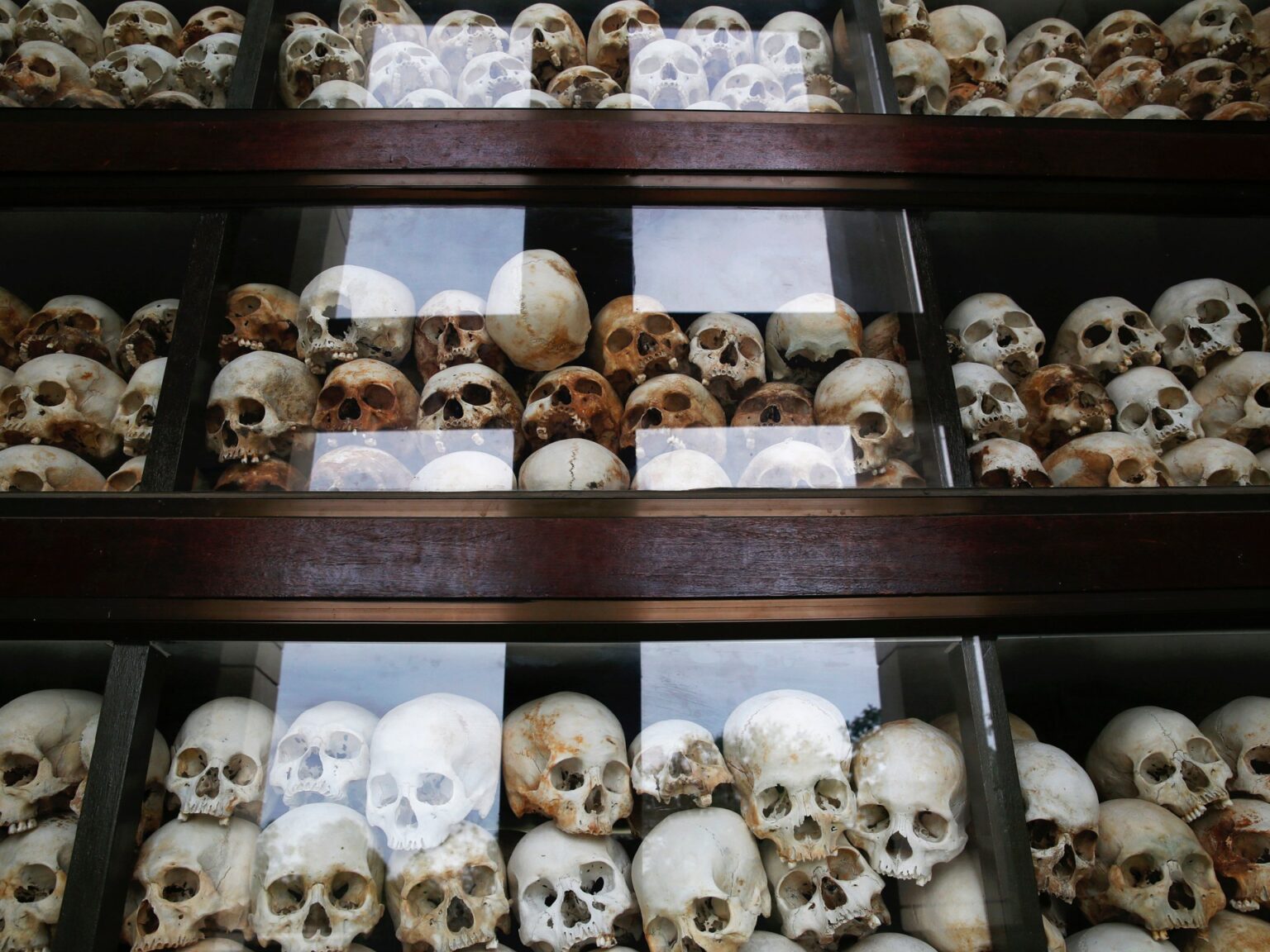

In less than four years under the Pol Pot government, between 1.5 and three million people were dead. They would also almost eliminate the rich cultural history and religion of Cambodia.

Many Cambodians were brutally killed in the “Khmer Rouge murder” fields, but much more died of starvation, illness and exhaustion in collective farms to build the rural utopia of the communist regime.

At the end of December 1978, Vietnam invaded the Cambodian deserters along Deide, demolishing the Khmer Rouge of Power on January 7, 1979. From this point, it is the popular knowledge of popular knowledge of the contemporary tragic history of Cambodia, choosing UPH-200000 Crimes Court in the Court in Phnom Penh Penh, where the former regimes leaders were in the trial.

However, for many Cambodians, instead of being relegated to history books, the 1975 Phnom Penh fall and the fall of the Jemer Rouge in 1979 remain alive and well, embedded in the Cambodian political system.

That tumultuous period of Jemer Rouge is still used to justify the long -term rule of the Popular Camboyian Party (CPP) in different ways since 1979, and the personal rule of the CPP leader his SEN and his family since 1985, to analysts. It was the now greatest leadership of CPP that joined the Vietnamese forces to expel Pol Pot in 1979.

While the memories of those times are fading, the control of the power of the CPP is as firm as in the decades as the end of the 1970s.

‘The creation of a political system’

The ruling CPP looks “themselves as El Salvador and the country’s guardian,” said Chhengpor, a policy researcher in the future group of experts in the forum in Phnom Penh.

“Explains the creation of a political system as it is today,” he said, and pointed out that the CPP has long done what they replace “to ensure that they are still there in the helmet … at any cost.”

Most of the Cambodians have now accepted a system where peace and stability matter above all.

“It seems that there is an unwritten social contract between the ruling establishment and the population that, while the CPP provides relative peace and a stable economy, the population will leave governance and politics to the CPP,” said Chhengpor.

“The general panorama is how the CPP is perceived in itself and its historical role in modern Cambodia. It is not so different from how the military establishment of the Palace in Thailand or the Communist Party in Vietnam they see their roles in their advice of respect.”

The CPP led a regime backed by Vietnamese for a decade, from 1979 to 1989, bringing an order related to Cambodia after the Jemer Rouge, even when the fighting persisted in many parts of the country when the Pot Pot combatants tried to control the control.

With support by decreasing the Soviet Union in the last days of the Cold War and an economic and an economic, Vietnam depleted the withdrawal of Cambodia, its Sen, by then the country’s leader, the field to celebrate the war of the elections. Part of an agreement to end retention retention. From 1991 to 1993, Cambodia was administered by the UN transition authority in Cambodia (UNTAC).

The Cambodian monarchy was formally restored, and the elections were held for the first time in decades in 1993. The last soldiers of Jemer Rouge surrendered in 1999, symbolically closing a chapter on one of the most bloody conflicts of the twentieth century.

Despite a path full of potholes, there was initial hope for Cambodian democracy.

The Royist United National Front for an independent, neutral, peaceful and cooperative party of the Cambodian party known for its acronym Funcinpec-Won the elections not administered in 1993. Faced with the defeat, the CPP took refuge the power of CEDE.

The late King Norodom Sihanauk intervened to negotiate an agreement between both sides that preserved the peace won and made the election a relative success. The international community gave a sigh of relief since the UNTAC mission in Cambodia had been the largest and most expensive at that time for the world body, and the UN Member States were desperate to declare their investment in the reconstruction of the nation a success.

Declaring jointly under a shared power agreement with CPP and Prime Ministers of Funcinpec, the unstable alliance of the former enemies held for four years until it ended in a fast and bloody blow for their Sen in 1997.

Mu Sochua, an exiled opposition leader who now directs the non -profit movement Khmer for democracy, told Al Jazeera that the resistance of the CPP to a democratic power transfer in 1993 continues to reverberate three Cambodia today.

“The failure of the transfer of power in 1993 and the agreement that the King made at that time … It was a bad business. And the UN left because to close the store,” he told Al Jazeera from the United States, where he lives intifiño being forced to Flee The.

“The transition period, the transfer of power … which was the will of the people, it never happened,” said Mu Sochua.

The end of war does not mean the beginning of peace

After the coup in 1997, the CPP did not lose power until 2013, when they were challenged by the broad popular Camboyian National Rescue Party (CNRP).

At the time of the next general elections in 2018, the CNRP was prohibited by politicians by the courts less than industrialists in the country, and many of the opposition leaders were forced to flee the country or ended in prison with political motivation.

Without obstacles by a viable political challenger, the CPP of his Sen won all the seats in the 2018 national elections, and all but five of the 125 parliamentary seats containing the latest general elections in 2023.

The CPP has also firmly aligned with China, and the vibrant free press of the country has closed, and civil society organizations feel silent.

After obtaining 38 years of power, his Sen took aside as prime minister in 2023 to give way to his son, his malet, a sign that the political machine led by CPP has his eyes in the dynastic and multigeneral government.

But new challenges have emerged in the decades of relative prosperity of the postwar period of Cambodia, great inequality and a unique de facto government.

The flourishing Microcredit industry of Cambodia intended to help Cambodians get out of poverty, but the industry has burned families with high levels of personal debt. An estimate places the figure in more than $ 16 billion in a country with a population of only 17.4 million and a gross domestic product (GDP) or $ 42 billion in 2023, according to World Bank estimates.

Even Chhengporen told Al Jazeera that there are signs that the government is taking note of these emerging problems and demographic changes.

The cabinet of its Manet is changing towards the “legitimacy based on performance” because they lack the “political capital” that was once awarded by the public to those who freed the country of the Khmer Rouge.

“The proportion of the population that recalls the Khmer Rouge, or that has usable memories of that period, is being reduced year after year,” said Sebastian Strangio, author or Cambodia of his Sen.

“I don’t think so [the CPP ‘s legacy] It is sufficient for the majority of the population born at the end of the Cold War, “Strangio told Al Jazeera.

Now, there seems to even be space for a limited amount of popular opposition, said the analyst still Chhengpora.

In January, Cambodian farmers blocked a main road to protest against the low prices of their assets, which suggests that there may be “some space” in the political system for the dissent located on community issues, he said.

“[It] It will be a struggle up for the fractured political opposition to prosper, not to mention the organization among the Titi and, much less, to have the hope of winning a general choice, “said Chhengore.

“However, there are indications that the CPP still believes in some way in the multi -party system and limited democracy in the way they have voice about when and how much democracy,” he added.

Speaking in the exile of the United States, Mu Sochua had a more dim vision of the situation of Cambodia.

The same month as the farmer protests in Cambodia, a former member of the Parliament of the Camboyan opposition was shot dead in a street light in a street in the capital of Thailand, Bangkok.

The shameless murder of Lim Kimya, 74, a double citizen of Cambodia-Frisch, remembered memories of the chaotic political violence of the nineties and early 2000s in Cambodia.

Peace and stability, said Mu Sochua, exists only on the surface in Cambodia, where the waters are still deep.

“If politics and space for people to get involved in politics do not exist, which dominates then is not peace,” he said.

“It remains the feeling of war, insecurity, or lack of freedom,” he told Al Jazeera.

“After the war, 50 years later, at least there is no bloodshed, but that only does not mean there is peace.”