In January of this year, Sharana Basava or Kapagal Village, in the district of Manvi Taluk or Raichur in northern Karnataka, left their home saying that he was meeting some acquaintances. A construction worker who also led an interested car to get to the end of the month, however, did not return home that day. His surprised family soon discovered that he had died for suicide. The 35 -year -old is survived by his parents, his wife Parvati and three young children.

Parvati alleges that Basava was pushed to take the extreme step due to the continuous harassment of the ‘collection agents’ of the microfinance companies that had lent him around ₹ 4 Lakh. She says that money was caused to meet the health needs of Basava’s parents and other household expenses, since their work and income had three. She was harassed and verbally abused since she had not paid some deliveries on time, she says.

Demanding justice, Plvati even sent him ‘mangalasutra’ (necklace that symbolizes his marital status) to the Interior Minister of Karnataka, Dr. G Parameshwara.

However, yours is not an isolated case in the state.

Jayashela, a 53 -year -old woman from Ambale’s village, finished her life in January while fighting the ₹ 5 Lakh who had erased two microfinance companies. She used loan money, with reimbursements scheduled in monthly installments of ₹ 20,000, to buy a cow and agricultural tools. When the cow became ill and died, Herbome three above.

In the last six months, 22 to 38 deaths have been reported in similar circumstances throughout the state.

By avoiding the linking of deaths directly with microfinance activity, government sources say that causes vary from family problems to land disputes and health problems.

However, tragic developments serve as a gloomy reminder or how the microfinance loan ecosystem, Meean, to empower millions in unattended communities, can sometimes become a death trap.

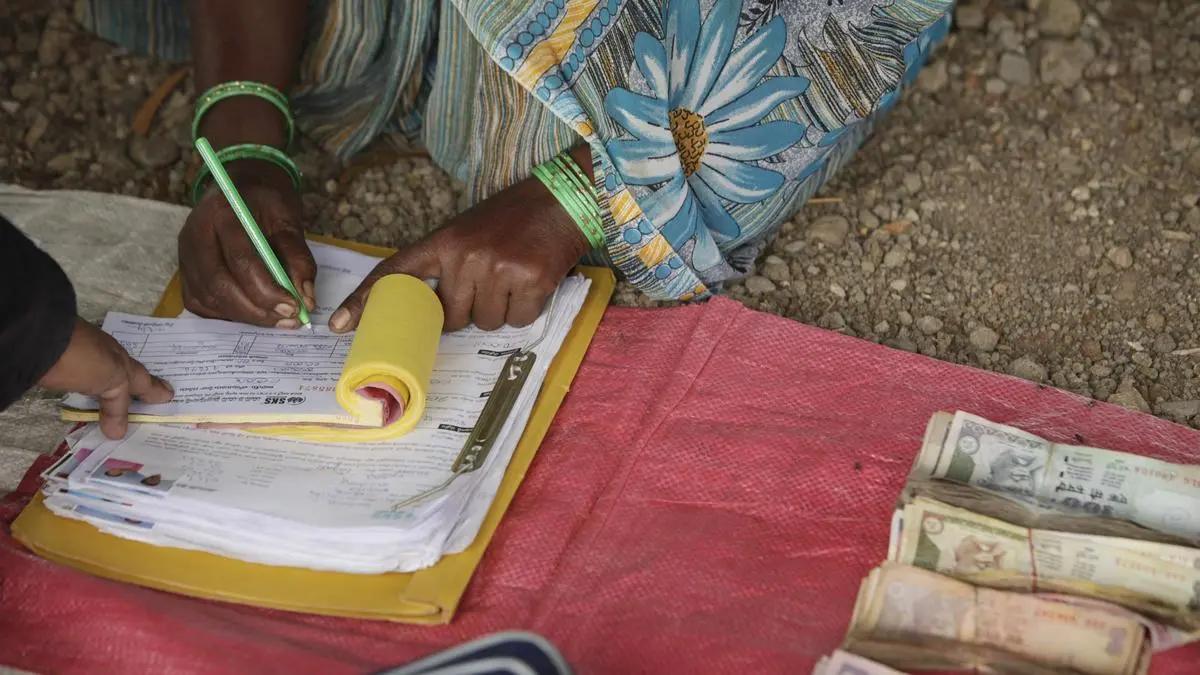

The gross loan portfolio of the microfinance institutions (IMF) in India was found in an amazing crore of 3.91 Lakh in the third quarter of fiscal year 2015, according to CRIF data. Only in Karnataka, support for IMFs in a million rupees, even around 63 Lakh of unique borrowers.

The IMF portfolio of the State increased from ₹ 16,946 million rupees in March 2019 to ₹ 42,265 million rupees in March 2024, according to the data of the Microfinance Industry Network (MFIN), an industrial organism.

Public pressure

In the midst of increasing anguish levels among borrowers, there is a violent reaction against the alleged aggressive collection tactics of IMFs; Industry actors, however, argue that personal or family problems, instead of financial problems, were promoting borrowers about the advantage.

Public pressure pushed the Karnataka government to act. In March, the State Assembly approved the Micro Loan and Small Loan bill (prevention of coercive shares), which proposes to completely comply with the borrowers of the payment loans, including interests, IMF tasks without a license and not registered.

Other states have also had their share of problems with microfinance activity. In 2011, Andhra Pradesh was started by more than 70 suicides, according to reports, linked to aggressive recovery tactics of IMF. This caused national outrage and a regulatory review.

Sks Microfinance, the leader IMF player, saw his purged administration and was possible through a fusion, under a new identity, with Indusind Bank.

Similarly, in Assam, in the period prior to the state elections of 2021, the political parties promised loan exemptions, which led many borrowers to stop payments. This triggered a financial crisis among the IMF. In response, the State introduced the Law of Micro Finance Institutions (Money Loan Regulation) of Assam to regulate loans and protect borrowers.

Worry about NPA

In Karnataka, IMFs, together under the Association of Microfinance Institutions of Karnataka (AKMI), blame the current crisis of “some bad apples”, which are not licensed and not regulated. They regret that the increase in non -compliance rates has led to an increase in non -yield or NPA assets.

In the district of Haveri, where 26 IMF have cumulatively disbursed loans worth ₹ 1,692 million rupees, Akmi says that payment rates have collapsed to 30 percent. “Previously, the reimbursement used to be 90-92 percent,” says a senior executive or Navachetan Microfinance Ltd, who requested anonymity. The suspects that fortified interests and local political leaders are encouraging breaches. This not only affects the credit scores of the borrowers, but also leaves high and dry genuine borrowers as IMF reduce loans, he adds.

Akmi’s concerns that organized IMFs are being with the same brush as flight operators per night, leading to growing loan criminals.

The Book of Cumulative Loans of the IMF in Karnataka hired ₹ 34,000 million rupees in December 2024 of ₹ 42,000 million rupees in March 2024 (excluding microfinance loans reflected in Banks portfolios), and is projected to slide more. The quartet

Recurrent problems raise awkward questions: are systemic failures integrated into the microfinance model? Is the foundation of the industry structurally flaved?

Recurrent Hicups?

Suresh Krishna, Former MD of Creditaccess Grameen, Co-Founder of Akmi and Mfin, and Now A Committee Member of the Self-Regulatory Organization Sa-Dhan, Points to Regulatory Loophles: “When the rbi lift the cap on Lenders, Lenders, Lenders, Lenders, Lenders, Lenders, Lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, lenders, had already neglected.

An industrial veteran, who requests anonymity, explains that while microfinance can be a disciplined and infallible system, their profitability attracts indisciplined players. “Interest rates are high. From abroad, it seems a very profitable business, and it is, if it is managed correctly. But if they run through, periodic crises can eliminate all profits.”

He adds that the structure of microfinance, equated with monthly or weekly fees, is incompatible with the needs of the borrowers who invest in small businesses. “Capital expenditure can be financed through longer-term loans such as micro-mortgages, but working capital still lacks adequate products. The industry must develop alternatives to loans based on EMI for companies.”

Corrective measures

To address the announceable problems that the microfinance sector impacts, industry agencies recognized by RBI MFIN and SA-DHAN have announced key reforms, as of April 1. A primary change is to limit the number of lenders by ravus to four reversals of the post-covid.

“People began to borrow from multiple sources, which led to excessive loans and the tension of managing multiple reimbursements,” says a senior AKMI official.

Short loan holdings exacerbate concerns, he adds. “Borrowers need a minimum reimbursement period of five years, instead of three years.”

Krishna says that unregulated players distort the market by making fun of industry’s code of behavior and resulting in aggressive recovery practices.

Looking to the future

Recurrent crises in the microfinance sector underline the urgent need for stronger safeguards, better designed loan products and narrower regulatory supervision.

To meet working capital needs, the sector must develop more flexible and friendly products for the company, a veteran industry advice.

Krishna adds that real -time credit monitoring could help prevent excessive loans. “The data of the credit office must be charged and accessible in real time, so the lenders know exactly how much a stroke of others has,” he says. And to ensure that customer rights are honored without fail, “there must be greater awareness about complaints repair systems in place,” he says.

More like this

Posted on April 13, 2025