It’s become common to rubbish Serious Economists, and given their track record, it’s not hard to see why. Among other reasons, the ones that have a better grasp on how the provisioning of society actually works are usually relegated to the heterodox wilderness. That is because they lost the plot. The purpose of mainstream economics is to defend the proposition that “free enterprise” systems will (or can be organized to, with the help of said right-thinking economists) to beat command and control systems, as in evil Commies. This was a legitimate concern since both Russia and China industrialized in a generation, accomplishments that gave capitalists pause.

The top editors at the Financial Times, such as Gillian Tett and its chief economics editor, Martin Wolf, are particularly subject to orthodoxy pressures despite having exhibited some independence of mind in the past. Wolf’s latest piece, The old global economic order is dead, makes two important observations despite getting wrapped around the axel in some other ways.1 I’ll simply focus on the good bits after an intro of the constraints under which someone like Wolf operates.

I have some sympathy for Wolf because in the runup to the crisis, he (based on the work of then capital markets editor Gillian Tett and the readings of John Authers) was early to be worried about the direction of travel and the lack of good information. After the crisis, Wolf was also pumping for serious reforms, promoting the campaign by Mervyn King, Paul Tucker, and Andrew Haldane at the Bank of England. One of their big agenda items amounted to a modern version of Glass Steagall, of separating capital markets trading from traditional banking. They lost after a hard fight to Treasury, which ‘natch was all in for the banksters.

However, Wolf is also hostage to his status at the pink paper’s de facto ambassador to the Serious Economist community. He always goes to Jackson Hole. He regularly moderates Big Deal economics panels or has one on one discussions. So he winds up not arguing with Ben Bernake’s ridiculous and self-serving savings glut thesis because he needs to get on with Bernanke. I’ve also seen Wolf interview Larry Summers at a conference (although “interview” does not give quite the right image of the dynamic. Before Summers I never saw someone fill a very large room with his ego). So some cognitive capture is inevitable.

Now to the two tidbits from Wolf’s latest. The first is on sectoral balances, something we discussed extensively here back in the day. From a 2010 post, fittingly with Martin Wolf’s name in the headline:

Martin Wolf, in today’s Financial Times, uses modern monetary theory (!), also known as the fiscal balances approach, to explain why calls for fiscal belt tightening are premature.

Let’s provide a little background, courtesy Rob Parenteau of the Levy Institute:

…if we divide the economy into three sectors – the domestic private (households and firms), government, and foreign sectors, the following identity must hold true:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance + Foreign Financial Balance = 0

Note that it is impossible for all three sectors to net save – that is, to run a financial surplus – at the same time. All three sectors could run a financial balance, but they cannot all accomplish a financial surplus and accumulate financial assets at the same time – some sector has to be issuing liabilities [borrowing].

Since foreigners earn a surplus by selling more exports to their trading partners than they buy in imports, the last term can be replaced by the inverse of the trade or current account balance. This reveals the cunning core of the Asian neo-mercantilist strategy. If a current account surplus can be sustained, then both the private sector and the government can maintain a financial surplus as well. Domestic debt burdens, be they public or private, need not build up over time on household, business, or government balance sheets.

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance – Current Account Balance = 0

Again, keep in mind this is an accounting identity, not a theory. If it is wrong, then five centuries of double entry book keeping must also be wrong.

Yves here. Many readers reject the message here instinctively. You cannot have the private sector save in aggregate AND have government run a surplus UNLESS you run a trade surplus. And the problem we have is:

1. The private sector in pretty much every advanced economy is deleveraging, as in saving. Most people, yours truly included, think that’s a good idea.

2. If those economies want to run government surpluses too, then they need to run pretty big trade surpluses

3. It is impossible for all countries to run trade surpluses at the same time.

4. Moreover, some countries that have been running large trade surpluses for quite a while (in particular China and Germany) are not willing to change course, at least not in the near future.

5. So if all these new hairshirt-wearers want to shirk public and private debt at the same time, some countries will need to run correspondingly large trade deficits (which also means they will experience rising private or public sector debt levels). There appears to be a dearth of candidates for this role.

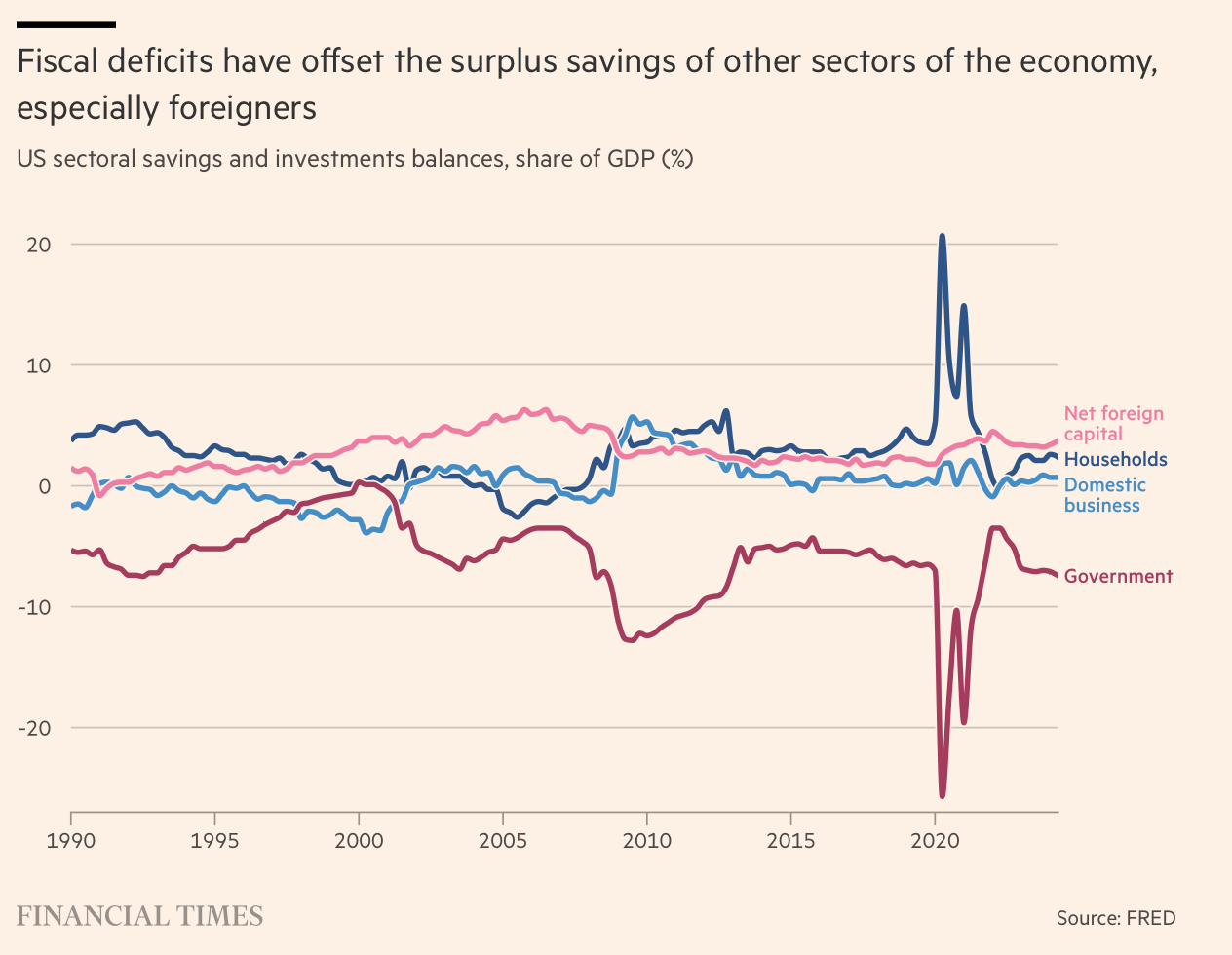

Wolf in his current post has a wee chart which shows (although Wolf does not call this point out) how the US managed to make this conundrum worse.

The understanding many have of the economy (based on the incorrect premise that investment comes out of pre-existing savings, as opposed to loan proceeds that banks can create from thin air) is that household savings fund business investment. That’s a big reason for the disquiet over government deficits…aren’t they crowding out business? No, because first, businesses set their return targets too high, so they will just about never invest enough to generate full employment. In fact, they WANT unemployment so as to keep wages down and be able to discipline labor. Second, our terrible government accounting system feeds the prejudice against government spending, since it does not create an income statement and balance sheet, which would differentiate spending from government investment.

But third, as we pointed out in a Conference Board Review article in 2005, The Incredible Shrinking Corporation, US companies in aggregate were not just under-investing but net saving, as in slowly liquidating. This tendency has gotten even worse via stock buybacks.

Wolf, having (per our 2010 post) having once-upon-a-time tried to argue against austerity, skips over the key issue:

Sectoral savings and investment balances are revealing indicators of this last challenge. Foreigners have been running a substantial savings surplus with the US for decades. US businesses have also been in balance or surplus since the early 2000s, while US households have been in surplus since 2008. Since these sectoral balances have to add to zero, the domestic counterpart of US current account deficits has been chronic fiscal deficits.

What you see, if you squint a bit, is consistent with the “Shrinking Corporation” article: companies had been borrowing to invest in growth. In aggregate, around 2003, they started engaging in the highly unnatural and ultimately destructive behavior of giving up on capitalists by investing in their companies and instead, for the most part, became obsessed with cost-cutting. You see government borrowing picking up the slack.

The related point, again not often enough made, is what “investments” are made matters. Household borrowing has been found to be economically unproductive. For governments, it matters over time whether investments are productive (clean water, good roads and bridges, cheap broadband, for starters) or are exercises in big-ticket pork, like our military.

The second useful point Wolf makes is on China’s unbalanced economy. The Manichean thinking cognitive bias among many readers is staggering. Just because the US has made a complete mess of its once-formidable advantages does not mean that China isn’t a source of instability too. From Wolf:

Michael Pettis is, in my view, correct that the world economy cannot easily accommodate a huge economy in which household consumption is 39 per cent of GDP and savings (and so investment) correspondingly huge. What is also clear is that the latter has also helped drive what the Rhodium Group judges a successful Made in China 2025 policy.

Many explicitly reject the idea that there is such a thing as overinvestment. Huh? Are you old enough to remember the dot-com era? The US produced a shit-ton of Internet businesses, as in way way more than the market would support, so most died. The US had another overproduction crisis in the railroad boom of the later 1800s, when promoters were able to launch rail lines, irrespective of the actual commercial potential, because they could make a killing on the stock trading. Some were even built duplicating barely successful or money-losing lines between the same city pairs.

Wolf points out that China has a large enough potential internal market to solve this problem. But the Chinese continue to save at very high rates. He notes:

China has the option of expanding domestic demand and so offsetting lost US demand. Matthew Klein responds, in his excellent Substack The Overshoot, that China has long had this option but has failed to use it. My answer is that China must now do so and thus will indeed choose to expand demand rather than accept a huge domestic slump. We shall see.

The reason Chinese save so much is the lack of social safety nets and worker protections, such as a minimum wage. And yes, China could readily solve this problem but Xi is hostile to it. As we wrote in 2023, incorporating a comment by PlutoniumKun (who follows the Chinese press as well as development literature):

China seems not just to be having what would be expected difficulty in changing from an investment/export led growth model to one with domestic consumption being far more important. China also appears to have an ideological, or one might say political problem in making this shift. Higher consumption would require lower savings rates. Not only do Chinese consumers not feel secure enough to do that (too much history of crises in China and its neighbors) but China under Xi is unwilling to implement the social safety nets that would encourage more spending.

I don’t want to take up too much time with this intro, but some relevant recent sightings. Note that Setser among other things is the man on dollar holdings and flows outside the US:

I suspected that parts of China’s top leadership objected to a household focused stimulus. Turns out the epicenter of opposition is Xi himself: “Xi sees such growth as wasteful and at odds with his goal of making China a world-leading industrial and technological powerhouse”

2/

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) August 27, 2023

Beijing’s mind seems made up — but Chinese policy makers have this backwards.

Using the central government’s clean balance sheet to support household demand would actually make it easier for households, property developers and local governments to delever.

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) August 27, 2023

A hypothesis: there can be no durably stable Chinese and global economy so long China’s national savings rate stays around 45% of GDP …

(note that, contrary to the IMF’s forecasts, savings has been rising since 2020 …)

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) August 28, 2023

China’s shoppers hesitate to spend big in face of deflation via @FT

🇨🇳

”Excess savings in China have increased in the first half of the year compared with the same period last year, and there is still a gap between pre-pandemic and current consumption” https://t.co/dvQvhP1lrU— Iikka Korhonen (@IikkaKorhonen) August 29, 2023

And now extracts from the points made by PlutoniumKun

But the reality is that a crisis is inevitable for any country pursuing an unbalanced growth model – i.e. by focusing on investment and exports over domestic/consumer led growth. This is baked into the standard model – and the Chinese are fully aware of this, and have been since at least the 1980’s and 1990’s when I started following (from afar) the Chinese economy from a development economics perspective. Back in the 1990’s the Chinese devoted very significant resources to studying the Japanese late 80s collapse, later the 1990s Asian crisis, and the multiple crashes which foiled numerous countries over the past century or more from crossing the threshold from upper-developing to developed country status. There is a line of thought among some China analysts that Xi was selected and given extraordinary powers specifically to deal with what was foreseen to be a very difficult transition from a the current development model to ‘developed’ status, which has always overtly been the holy grail for the CCP.

I don’t think there is much doubt that the current situation in China is very serious. In my opinion, the housing crisis is a symptom, not the cause of the current problems (in reality, the Chinese economy started showing signs of strain even before Covid). The core problem being several decades of internal debt build up and chronic mal-investment along with an overdependence on rising property values to underpin spending at a local level. But the housing issue alone is gigantic – by any objective measurement it is vastly greater as a proportion of the economy’s size than the Irish and Spanish crashes of 2007-9. When you add in demographic issues and climate induced strains, this is potentially much more than just a cyclical downturn.

It is highly unlikely for there to be a financial crash as the Chinese banking and finance model is very different from in the west…But it is increasingly recognized within China (this is very obvious reading between the lines in various statements from Beijing) that the current model has finally run out of steam and needs fundamental overhauling.

The problem is that this has been pretty obvious for some time, but despite numerous policy statements going back at least 2 decades (the big ‘change’ was supposed to happen after the 2008 Olympics), very little has been done…There has to be a very significant transfer of wealth to ordinary citizens through higher wages and better social welfare provision in order to boost consumer spending (one of the few things orthodox and heterodox economists agree on when looking at China). And as for debt – in theory, this is a simple problem to address (i.e. monetize/forgive it in one form or another), but there appears to be an unwillingness to even discuss this option within high level circles in China.

The irony to me is that having studied the Japanese crash intensively, the Chinese may somehow manage to replicate exactly the mistakes the Japanese made….

While it can be argued that the current property/investment boom is not as bad in China as it was in Japan, in other respects the Chinese economy may be a lot weaker than Japan was at the time – for all its modernity, China is still essentially a poor country – significantly poorer than, for example, Russia or Turkey, and probably not even matching Mexico. What is unique about China is its enormous size, which allows it to mobilize resources and dominate economic sectors in a way small developing countries can’t. But then again, this has never helped India, which also has some very advanced technological sectors.

The other huge problem – ironic given demographic problems – is youth unemployment. This seems to be a characteristic of fast growing export-led economies once they rise above the sweatshop levels of development – both Japan and South Korea have had huge problems in keeping up employment levels even at times when their economies have been seen to be healthy when measured in GNP. In simple terms, I don’t think you can keep up a high level of employment if you insist on suppressing wages and consumer demand. But this is integral to an export/investment model of development…

A few years ago, I would have been fairly confident that the CCP could pull it off, especially with someone as impressive as Xi at the helm. But more recently there are increasing signs of inept leadership, groupthink and poor decision making at higher levels of government in Beijing, going right to the top. There is a lot of rot among our leadership classes everywhere, not just in the west.

So again, a warning against black and white thinking. Just because the US is now terribly led and China has much more competent people in charge, as well as many technological advances of which it can be very proud, does not mean it cannot also be hostage to economic idea and/or social values that are keeping it from executing seemingly obvious solutions to its economic pressures.

____

.sup>1 There is a BIG complicating factor with respect to the data Wolf relied on at the top of his piece, which is also the foundation of the US tariffs policy. Mind you, I am not suggesting with the information below that the US does not have a big balance capital account surplus, but that reliance on multinational accounting data that shifts revenue to tax havens like Ireland overstates it. This is the 50,000 foot version of the argument from hidden wealth/tax evasion maven Gabriel Zucman; he has some more recent papers I need to mine to properly present his findings. The author who made this summary argues Zucman *must* be wrong, hence the need to look at later work (this sort of thing reminds me of other *musts* like US housing prices could never decline on a nation-wide basis). So:

Economist Gabriel Zucman’s paper “The Missing Wealth of Nations” proposes that a substantial part of the large U.S. net debt of the last 15 years is actually accounted for by U.S. tax evaders who have opened accounts in foreign tax havens, and then have reinvested their money in the United States. Such investments would look like foreign investments in the United States, but would actually be U.S. domestic investments. Zucman concludes that as a result, the U.S. capital account surplus must be lower than reported.